The Denmark Deception: How HHS Called an Outlier “Consensus”

The Gist: The Trump administration cut childhood vaccine recommendations from 17 diseases to 11, claiming it aligned with “international consensus.” That’s false. Most developed nations recommend vaccines for 12-15 diseases. Denmark—the single country they modeled our new schedule after—recommends 10, making it the most minimalist schedule of any developed nation. Even Denmark’s Nordic neighbors vaccinate against more diseases. This wasn’t alignment with peer nations. It was finding the one outlier that matched a predetermined outcome and calling it consensus.

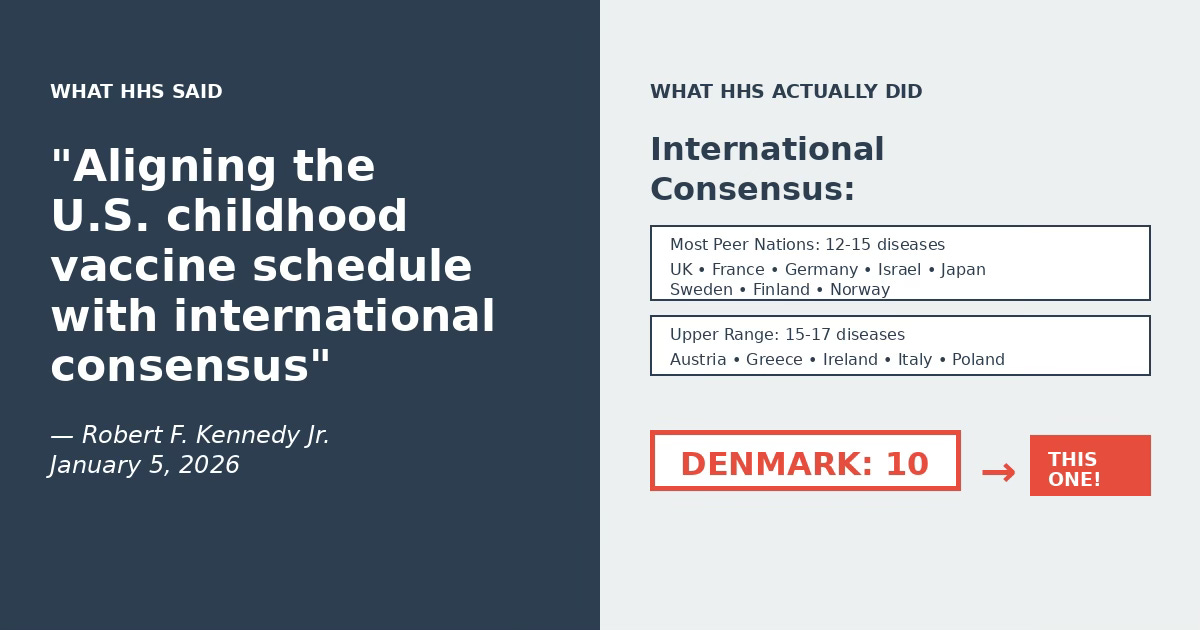

On January 5th, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. announced the CDC was cutting childhood vaccine recommendations from 17 diseases to 11. He called it “aligning the U.S. childhood vaccine schedule with international consensus.”

Here’s what international consensus actually looks like. Most developed nations recommend vaccines for 12-15 diseases:

UK: 12-15 diseases

France: 12-15 diseases

Germany: 12-15 diseases

Israel: 12-15 diseases

Japan: 12-15 diseases

Sweden: 12-15 diseases

Finland: 12-15 diseases

Norway: 12-15 diseases

Greece: 15+ diseases

Ireland: 15+ diseases

Italy: 15+ diseases

Poland: 15+ diseases

The European CDC tracks vaccine schedules for 30 countries. Exactly one recommends vaccines for just 10 diseases.

Denmark.

Even Denmark’s Nordic neighbors—countries with similar healthcare systems and similar populations—vaccinate against more diseases than Denmark does.

So when HHS claims the US was “a global outlier” for recommending too many vaccines, understand what they’re doing. We were at the upper end of the range. Now we’re at the bottom, past most peer nations, adopting the most minimalist schedule any developed country uses.

They found the one country that matched their predetermined outcome and called it consensus.

“Aligning with peer nations” sounds evidence-based. Like they did a comprehensive review and found where most countries land. They didn’t. They picked the extreme low end and presented it as the middle.

Here’s how this actually went down: Someone with dual US-Denmark citizenship presented to the CDC’s advisory committee suggesting fewer vaccines would reduce aluminum exposure in kids. A major Danish study already examined this and found aluminum from vaccines isn’t harmful. Kennedy demanded the journal retract it, called it pharmaceutical industry propaganda. They refused.

Then Trump issued a memo directing health officials to align with “peer nations”—specifically mentioning Denmark.

Denmark’s situation:

Universal healthcare

Guaranteed access to medical care

Low baseline disease prevalence

System catches illness early

We have 330 million people. No universal healthcare. Higher childhood obesity rates, higher asthma rates, more kids at higher risk for complications from diseases Denmark doesn’t worry about as much.

The numbers: Before routine chickenpox vaccination, the US had about 4 million cases annually. Now it’s under 150,000. Denmark doesn’t vaccinate for chickenpox. They see 60,000 cases a year in a population 1/55th our size.

Last year, 300 American kids died from flu. Eighty-nine percent weren’t vaccinated. The flu vaccine just moved from universal recommendation to “shared clinical decision-making.”

This didn’t go through the normal process. The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices is supposed to review evidence, hold public meetings, evaluate US-specific disease patterns and healthcare realities. Instead, an acting CDC director signed a decision memo accepting recommendations from an assessment that looked at 20 countries and chose the outlier.

No cited research. No public input. Just the outcome Kennedy wanted wrapped in language about international best practices.

California, New York, and Illinois have already said they’re ignoring the new federal guidance. They looked at their actual populations and disease burden.

I’ve spent three decades watching federal agencies use selective data presentation to justify decisions they’ve already made. Find the answer you want first, then locate the one data point that supports it. Present that single data point as if it represents the norm.

That’s what happened here. When you use “international consensus” to describe adopting the single most extreme position available among peer nations, you’re not doing policy analysis. You’re running PR.

Every country builds its vaccine schedule based on its own disease patterns, healthcare infrastructure, population demographics. Nobody just copies another country’s homework.

That’s not what this is either, despite the framing. This is predetermined outcome, selective citation, bureaucratic language designed to obscure rather than clarify.

You can agree or disagree with reducing childhood vaccine recommendations. But call it what it is. Don’t pass off selective citation as international consensus and expect people not to notice.

I use AI as a research and editing assistant—the same way I’d use a good reference book or a sharp editor. Every word published here is reviewed, verified, and approved by me. The perspective, accuracy, and editorial decisions are mine.