They Promised Housing. They Built Garden Sheds.

The VA’s answer to a federal court order: 800 eight-by-eight-foot boxes on a campus donated 137 years ago to house disabled veterans.

The Gist

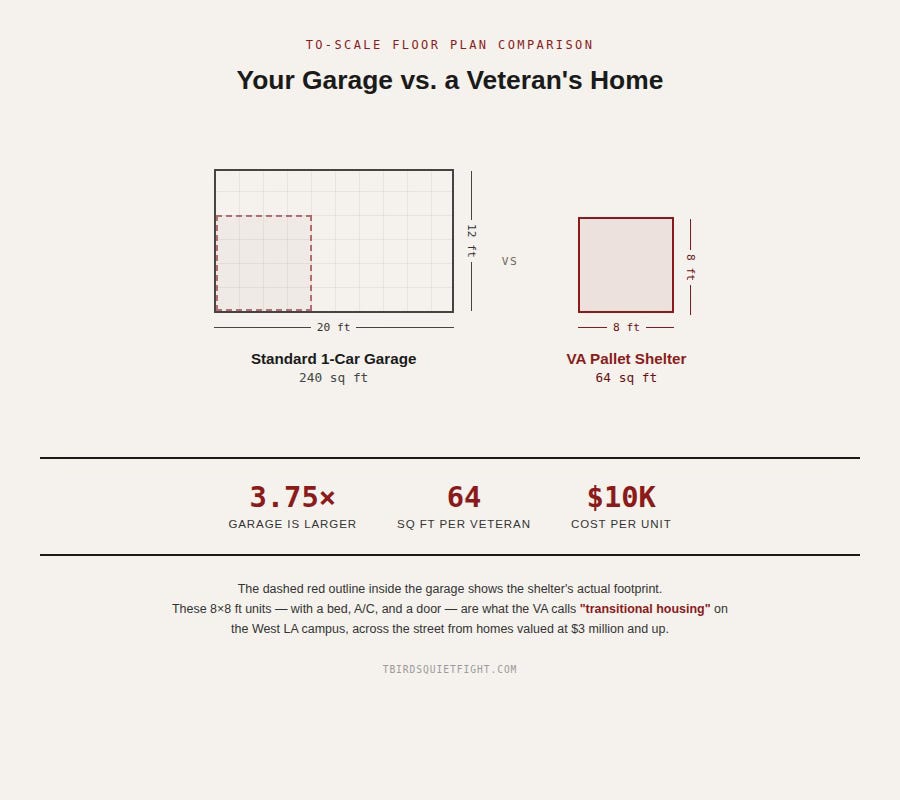

A federal court ordered the VA to build thousands of housing units for homeless veterans on its 388-acre West Los Angeles campus — land donated in 1888 specifically for that purpose. The VA’s response? Up to 800 eight-by-eight-foot sheds. No in-unit kitchen. No in-unit bathroom. Not ADA-accessible. Meanwhile, portions of the same campus remain leased to a private prep school and UCLA’s baseball team. The executive order promising 6,000 units has no clear plan, no timeline, and is being implemented by an agency that just cut tens of thousands of staff. This isn’t a housing plan. It’s a press release dressed up as compliance.

In 1888, Senator John Percival Jones and Arcadia Bandini de Stearns Baker donated 300 acres of prime West Los Angeles real estate to the federal government. The condition was simple: use it to house disabled veterans.

One hundred and thirty-seven years later, Air Force veteran George Fleischman sits in one of those 8x8 sheds on that same campus — where he’s been for over three years in what the VA calls “temporary” housing. He uses a wheelchair. He described it as living in the place where you’d keep your lawn mower.

There’s the country’s promise to veterans and what it delivers. And there’s the gap. It’s not getting any smaller.

What the Court Ordered vs. What the VA Built

In September 2024, U.S. District Judge David O. Carter issued a ruling that didn’t mince words. After years of litigation — the Powers v. McDonough lawsuit filed by disabled veterans in 2022 — he ordered the VA to build 1,800 permanent supportive housing units and 750 temporary units on the West LA campus.

In December 2025, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the order and went further, finding that the VA had “strayed from its mission.”

Then came the January 2026 court hearing where the VA unveiled its compliance plan: hundreds more 8x8 sheds.

The veterans’ attorney, Roman Silberfeld, told the court there was a “disconnect” between what they’d fought for and what the VA proposed. Judge Carter himself questioned whether any veteran on Skid Row would see a move to a shed as an upgrade.

These aren’t tiny homes. They’re 64 square feet. No in-unit kitchen or bathroom — veterans rely on communal shower and restroom facilities outside the shed. They’re searched going in and out. The existing units have proven difficult for anyone using a wheelchair or walker. And “temporary” stays have stretched into years.

They’ve Already Burned Down Once

On September 9, 2022, a lithium battery overheated inside one of these same Pallet shelters on the West LA VA campus. Within minutes, the fire jumped from unit to unit. By the time LAFD arrived, 11 shelters were ablaze.

The damage:

12 tiny homes destroyed. 10 more damaged. Twenty-one veterans and one spouse displaced.

$160,000 in total damage — more than the cost of building 16 new units at $10,000 each.

Pallet shelters carry a Class C fire rating — the lowest classification. The LAFD does not test them for flammability.

Fire extinguishers ran out after what one resident described as “a couple of squirts.”

No fire hydrants at the site. LAFD had to manually extend a supply hose to the nearest one.

Emergency exits were dog doors — small flaps at floor level. Some were blocked by electrical wiring. Many residents didn’t know they existed. These are disabled veterans. Some are in wheelchairs. A dog door at floor level isn’t an escape — it’s a death trap with a hinge.

No evacuation plan was given to residents when they moved in.

Veterans lost medications, housing vouchers, CPAP machines, and clothing. One veteran grabbed his phone and wallet. Everything else burned.

Fire trucks had difficulty maneuvering because the units were packed so tightly together.

It wasn’t an isolated incident. Pallet shelters had already burned in Banning, Santa Rosa, and Oakland — all before the West LA fire. After the Banning fire destroyed 20 units, Pallet quietly changed the wall materials. The company said the change had nothing to do with fire safety. A fire marshal who reviewed the new material told Curbed it was no less flammable.

After the West LA fire, the VA announced safety improvements: new smoke alarms, a dedicated e-bike charging station, wider access roads, two additional fire hydrants “closer to” the site, and new rules banning extension cords and battery charging inside units. What the VA did not do: upgrade the shelters themselves, install sprinkler systems, change the manufacturer, or improve the fire rating of the structures veterans sleep in every night.

Veteran advocate Rob Reynolds, who arrived on scene that night, told Spectrum News: “The veterans should be inside buildings with sprinkler systems. This wouldn’t have happened. They shouldn’t even be in tiny homes.”

Now the VA wants to build hundreds more of them.

The Campus That Was Stolen in Slow Motion

This didn’t happen overnight.

The West LA VA campus once had a chapel, a theater, a billiard hall. It housed roughly 6,000 veterans. It was, by all accounts, exactly what the donors intended.

Then, starting in the 1970s, the VA began leasing chunks of the property to outside interests. UCLA got a baseball stadium. The Brentwood School — a private K-12 where tuition runs $55,700 a year — got athletic facilities. Oil companies got drilling rights. The VA’s own Inspector General concluded these agreements did not primarily benefit veterans.

While private interests used the campus for profit and prestige, veterans pitched tents on the sidewalk outside the gates. “Veterans Row” along San Vicente Boulevard became a national embarrassment — and a rallying point for the lawsuit that followed.

The Ninth Circuit’s December 2025 ruling invalidated many of those private leases. But it notably let UCLA keep its arrangement. And the VA has been slow to reclaim the rest.

The Executive Order: Big Promise, No Blueprint

In May 2025, President Trump signed Executive Order 14296 establishing the “National Center for Warrior Independence” on the campus, calling for housing for up to 6,000 veterans by January 2028.

The rhetoric was strong. The specifics were nonexistent.

VA Secretary Doug Collins had 120 days to present an action plan. That deadline passed in September 2025. As Task & Purpose reported in December, no full plan has been released — the VA missed its own deadline. The LA Times reported in January 2026 on notices for renovating two buildings on the campus, the first concrete details to emerge eight months after the order was signed.

The 6,000 figure itself raises questions. Current estimates put LA’s homeless veteran population at roughly 3,050, per the 2025 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count. The executive order envisions bringing veterans from across the country to one campus. Critics — including veteran housing advocates quoted by The Independent and NPR — have warned this could concentrate thousands of vulnerable people in one location without adequate infrastructure, creating a warehouse rather than a community.

And the math doesn’t work on the backend either. The VA told the court it has funding to complete temporary housing by end of 2026, but not the permanent housing portion. Temporary housing, in this context, means more sheds.

The DOGE Contradiction

Now watch the other hand.

The same administration issuing executive orders about veteran housing launched DOGE-driven cuts that hollowed out the VA’s capacity to deliver on those promises. An internal VA memo obtained by Government Executive in March 2025 called for slashing 83,000 positions — returning staffing to pre-PACT Act 2019 levels. Military.com, Bloomberg, and the VA’s own chief of staff confirmed the target. After sustained backlash, the VA scaled back to 30,000 positionsthrough attrition, according to AFGE. As if cutting fewer people somehow made it acceptable.

But it wasn’t just headcount. The administration gutted the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness. It suspended the Veterans and Community Oversight and Engagement Board — the very body charged with overseeing implementation on the West LA campus.

You can’t build 6,000 housing units while firing the people who process the paperwork, manage the construction, and coordinate the services. They promise a “Beacon of Hope.” They deliver a 64-square-foot fire trap — no bathroom, no kitchen, just a shed. But “Beacon of Hope” makes better copy.

The Voucher Dead End

Even for veterans who make it through the shed pipeline and get approved for permanent housing, the path doesn’t end. It just hits another wall.

As of early February 2026, hundreds of HUD-VASH vouchers — housing vouchers created specifically for veterans — sit unused in Los Angeles because landlords won’t accept them. Army veteran Charles Nelson, his wife, and their young son went through the sheds, then a hotel, then finally got a voucher. They were among the lucky ones.

The voucher system only works if there’s housing on the other end. In LA’s rental market, that’s increasingly a fiction.

What This Really Is

I’ve been documenting VA patterns for 29 years. This one is familiar.

The VA gets caught failing veterans. Courts or Congress order a fix. The VA complies on paper with the cheapest, fastest, most minimal response it can get away with. Officials issue statements about their “commitment.” The press cycle moves on. Veterans keep waiting.

The sheds aren’t a housing solution. They’re a compliance strategy.

The executive order isn’t a plan. It’s a talking point.

And the 388 acres donated in 1888 to house disabled veterans still hosts a prep school’s athletic complex — while the veterans those acres were meant for live in boxes the size of a parking space.

What You Can Do

If you’re a veteran or family member:

The Powers v. McDonough case is back before Judge Carter for implementation. Watch for updates from the veterans’ legal team.

Contact your congressional representatives and ask specifically what they’re doing about the West LA campus.

If you’re an advocate or journalist:

The VA’s 120-day action plan for the National Center for Warrior Independence was due in September 2025. Where is it? FOIA it.

Track the private leases. Which ones have been terminated? Which are still active?

If you’re a voter:

Don’t let anyone claim credit for “solving” veteran homelessness by building sheds. Demand permanent housing with real services.

Ask candidates whether they support fully funding the court-ordered housing — permanent units, not emergency shelters rebranded as progress.

The West LA VA campus is the most visible example, but the pattern repeats nationwide. When the country decides veterans deserve housing, it means apartments with in-unit kitchens and bathrooms and support services — not lawn mower sheds with a new coat of paint.

If this piece was useful, share it. The veterans living in those sheds can’t amplify their own stories from inside an 8x8 box.

Make the Call

A phone call takes two minutes. Congressional offices tally every one. If enough people call about the same issue in the same week, staffers flag it for the member. That’s how priorities get made.

Who to call:

Your own U.S. Representative and Senators — they work for you. Find yours here.

Rep. Mike Bost (R-IL) — Chairman, House Veterans’ Affairs Committee: (202) 225-5661

Sen. Jerry Moran (R-KS) — Chairman, Senate Veterans’ Affairs Committee: (202) 224-6521

Capitol Switchboard (connects to any member): (202) 224-3121

Script 1: If you’re a veteran or military family member

“Hi, my name is [NAME] and I’m a [veteran / military spouse / family member of a veteran] in [STATE]. I’m calling about the VA’s plan to house homeless veterans in 8-by-8-foot Pallet shelters at the West LA VA campus — the same shelters that caught fire in 2022 and burned 12 units in minutes. These carry the lowest fire safety rating available. Emergency exits are floor-level flaps that a veteran in a wheelchair can’t use.

A federal court ordered permanent housing. The VA is responding with sheds. I’m asking [MEMBER NAME] to demand that the VA provide construction timelines for permanent, ADA-accessible housing units — not emergency shelters rebranded as compliance — and to hold oversight hearings on the West LA campus plan.

I’d like to know the [Congressman’s / Senator’s] position on this. Thank you.”

Script 2: If you’re a concerned citizen

“Hi, my name is [NAME] and I’m a constituent in [STATE]. I’m calling about the VA’s response to a federal court order requiring housing for homeless veterans at the West LA campus in Los Angeles. Instead of permanent housing, the VA is proposing hundreds of 64-square-foot sheds with no kitchen, no bathroom, and no sprinkler system. The same shelters caught fire in 2022 — 12 units burned in minutes.

I’m asking [MEMBER NAME] to support oversight hearings on the West LA VA housing plan and to push for permanent housing construction with real timelines, not temporary shelters that have already proven unsafe.

Thank you for your time.”

Tips:

You don’t need to be an expert. You just need to be a constituent.

If you get voicemail, leave the message. It still gets counted.

Call during business hours (9 AM – 5 PM Eastern) for the best chance of reaching a staffer.

Be polite, be brief, and state your ask clearly.

If a staffer asks follow-up questions, it means they’re taking notes. That’s good.

Why calls matter more than emails:

Congressional offices rank constituent contact by perceived effort and urgency. Here’s how they actually process what you send:

Phone calls get logged in real time by issue and position (for/against). A staffer marks it in their system the moment you hang up. When a member asks “what are people calling about this week,” your call is in that count. High volume on a single issue in a short window triggers a staff briefing. This is the most effective single action you can take.

Personal emails (not form letters) get read, categorized, and usually receive a response — but they sit in a queue. Most offices process constituent mail in batches. Your email might not get logged for days. It still counts, but it doesn’t create the same real-time pressure as a ringing phone.

Form emails and petitions (pre-written “click to send” campaigns) get the lowest weight. Offices batch-count them. They know you clicked a button. It’s better than silence, but staffers treat one personal phone call as worth more than dozens of form emails.

Letters to the editor in your local paper punch way above their weight. Congressional offices have staff assigned to clip and track local media mentions of their boss. One published letter is perceived as representing 100+ constituent concerns — because it’s public, it influences other voters, and it can get picked up by larger outlets.

Op-eds in local or regional papers get flagged immediately and often become talking points in internal staff briefings.

The most effective combination: Call first. Follow up with a personal email. Then write a letter to the editor. Each one escalates the pressure through a different channel.

Go Deeper

Write a Letter to the Editor (10 minutes — worth 100 phone calls in perceived impact)

Most local papers accept 150–200 word letters. Mention your representative by name. State your veteran status if applicable. Stick to facts from this article.

Localize it — mention your rep by name and your nearest VA facility

Keep it under 200 words

Editors prioritize veteran voices on veteran issues

Don’t submit the same letter to multiple papers simultaneously

Contact Your VSO

If you’re a member of VFW, DAV, American Legion, VVA, IAVA, or any other Veterans Service Organization — contact your local chapter and ask what their position is on the West LA housing plan. VSOs have lobbying power. Use it.

Share This Article

Forward it. Post it. Print it. The veterans affected by these decisions often can’t amplify their own stories. You can.

About This Publication

Tbird’s Quiet Fight is independent investigative journalism focused on VA policy, veteran benefits, and government accountability. Published by the founder of HadIt.com, one of the oldest veteran-run VA claims communities online (est. 1997).

Tips and sources: ipersist@tbirdsquietfight.com (encrypted options available on request)

Support this work: Subscribe to TQF | Support HadIt.com

I use AI as a research and editing assistant—the same way I’d use a good reference book or a sharp editor.

For Press and Advocates

Story tips or collaboration:

Tbird (TQF / HadIt.com): ipersist@tbirdsquietfight.com

Congressional oversight contacts:

House Veterans’ Affairs Committee: (202) 225-9756 | veterans.house.gov

Senate Veterans’ Affairs Committee: (202) 224-9126 | veterans.senate.gov

Investigative journalists covering VA/veteran policy:

Suzanne Gordon — American Prospect

Jasper Craven — American Prospect

Nikki Wentling — Stars and Stripes

Leo Shane III — Military Times

Quil Lawrence — NPR

Abbie Bennett — Military.com

Veteran advocacy organizations:

Government watchdog resources:

USAspending.gov (track federal contracts and grants)

Sources: Los Angeles Times, Task & Purpose, LAist, Spectrum News, Military.com, Government Executive, Bloomberg, AFGE, Knock LA, Stars & Stripes, court filings in Powers v. McDonough (C.D. Cal. Case No. 2:22-cv-08357), White House Executive Order 14296 (May 9, 2025), Federal Register (90 FR 20369), VA safety protocol press release (Oct. 2022), Invisible People, Planetizen, VA Office of Inspector General reports, Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruling (December 2025), 2025 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count.

I use AI as a research and editing assistant—the same way I’d use a good reference book or a sharp editor. Every word published here is reviewed, verified, and approved by me. The perspective, accuracy, and editorial decisions are mine.